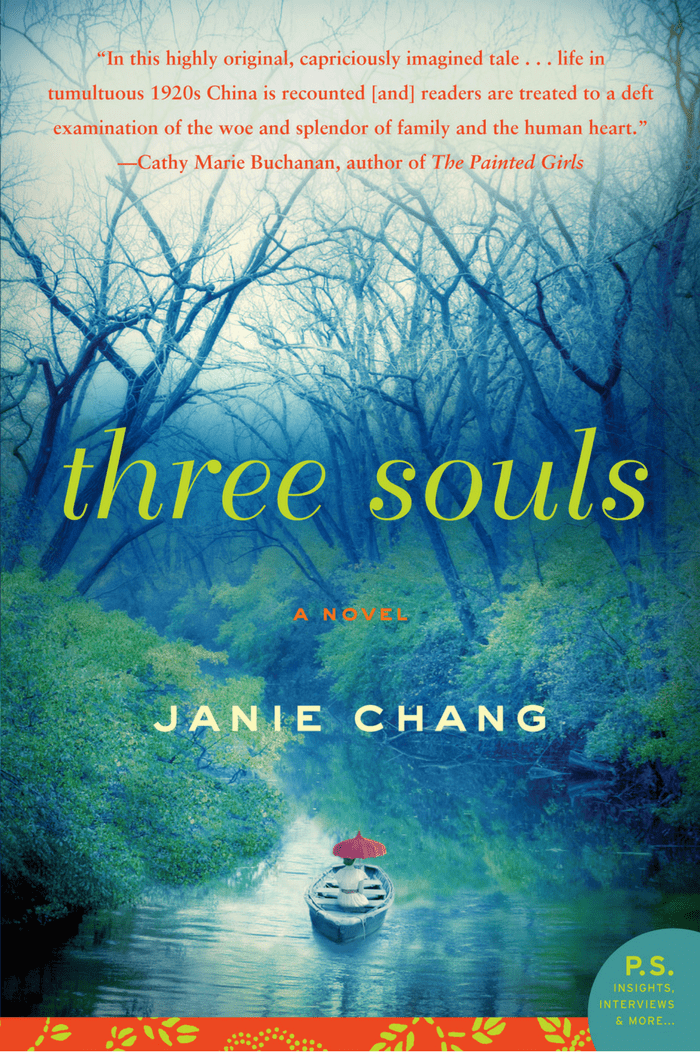

Three Souls

Enjoy the first chapter

Chapter One

Pinghu, China - January 1935

We have three souls, or so I’d been told.

But only in death could I confirm this.

The moment the priest spoke the last prayer and sealed my coffin, I awoke and floated upward in a slow drift of incense smoke, until I could travel no farther. I settled in the rafters of the small temple, a sleepy wraith perched in the roof beams. I had knowledge, but no memory. My first thoughts were confused, for clearly this was the real world. But surely I no longer belonged here. When would I take my journey to the afterlife?

Below me, pale winter sunlight from an open doorway illuminated the temple’s dark slate floors. Men and women in white robes crouched in front of an altar stained by decades of burning incense sticks. Noise assailed me from all directions. The tapping of woodblock instruments, the wailing of paid mourners, the chanting of acolytes. On the altar, a wooden tablet gleamed, gold-painted characters carved into its newly varnished surface. An ancestral name tablet, carved for a family shrine.

Song Leiyin. Beloved Wife. Dutiful Daughter.

I recognized that name. My name.

It was when the priests had finished their chanting that I saw my souls for the first time, three bright sparks circling in the air beside me. They were small, shining, and red as embers, but I knew that to the living they were as invisible as motes of dust.

One of the sparks floated in a lazy arc to rest atop the varnished tablet. A delicate rustling at the back of my mind said this was my yang soul. I could feel its presence, stern and uncompromising. My yin soul wafted down to settle on the coffin, a careless, almost impudent movement. My hun soul stayed beside me, watchful as a cat in a strange neighbourhood.

I turned to my hun soul, a question forming in my still-sleepy mind, when a small, pale face in the crowd below caught my eye. A little girl in mourning robes of white, white ribbons woven through her braids. She knelt behind a man bent so low with weeping his forehead touched the slate floor. The girl shuffled on her knees and the elderly woman beside her put a warning hand on her back. Obediently the little girl stooped down again, her expression blank but for the slightest quiver of her lips. Her dark eyes were dull and rimmed with red. They should have been bright, alive with curiosity.

How did I know that about her eyes?

Memory flickered and I recognized the little girl. My daughter. Weilan. She was so still, so silent. I snapped into wakefulness and in the next moment, I was beside her on the slate, my arms around her thin shoulders.

Mama is here, my precious girl. I’m still with you. But I couldn’t feel her. I drew back, suddenly cautious. I didn’t want to frighten her. I was dead.

She took no notice of me and that made me weep, my relief struggling with disappointment, for although I longed to hold her, I didn’t want to give her nightmares about her mother’s ghost. I stayed kneeling beside her, whispering all the pet names I used to call her: Small Bird, Sesame Seed, My Only Heart.

I hoped for a tiny gap between our worlds, a crack that would allow my comforting thoughts to reach her even if words could not. She was only six, so young to be motherless. Who would listen to her chant her times tables now and rub her cold hands on winter days? Who would arrange a marriage for her and teach her how to embroider cloth slippers as gifts for her husband’s family?

A restless, elusive tugging sensation told me I didn’t belong in this world, but I vowed to resist for as long as possible. If there was any way I could take care of my child, even if I couldn’t be seen or felt or heard, I wouldn’t abandon her until it became impossible for me to stay.

Borne aloft on the sturdy shoulders of hired mourners, my coffin left the courtyard. I followed, drifting beside my daughter as the funeral procession travelled through the streets of the town, my yin soul riding on top of the coffin. Beside my final resting place, I watched the ceremonies. The man who had been weeping arranged food offerings in front of the grave. Weilan lit a bundle of incense sticks, her small hands nearly blue with cold.

Tense and anxious, I watched as the coffin was placed in its grave. Surely once my body was buried, I would be snatched away to the afterlife.

But nothing happened. I was still here.

I returned to town with the funeral cortège, but my yin soul remained behind at the grave, and in my mind’s eye it shared with me what it saw. Workers were piling earth into a smooth mound on top of my burial spot.

When they finished, however, I didn’t drift upward, nor did my consciousness fade into oblivion. When was I supposed to begin my journey to the afterlife?

At the front gates of the estate, fewer than a dozen people entered, all that remained once the mourners had been paid off.

“Come, Granddaughter,” said the old woman. Her voice sounded tired, strained but kind. This was, had been, my mother-in- law. She would be the one to bring up my daughter now. “I told Old Kwan to have some sweet-date soup waiting for us. Let’s go and warm up in the dining room.” She led Weilan away.

I stood waiting by the temple, my mind full of questions. Finally my yin soul returned, sliding along a thin shaft of winter sunlight. It joined the two other sparks in a slow circling above the altar.

I’m dead and buried, I said to them. Am I not supposed to leave this earth now? Or will the gods let me stay to watch over my child?

But they ignored me and I drifted among the rafters of the temple, silent and perplexed.

My souls spiral down and come to rest on the altar.

We are ready now, says a stern voice, and there is a taste of mustard at the back of my tongue. My yang soul. Although his red spark remains balanced on the wooden tablet, an elderly man wearing a round scholar’s cap appears beside the altar. He resembles my grandfather as I’ve seen him in photographs, with steel-rimmed glasses and a goatee. He is dressed in a high-necked changshan gown of deep blue silk over loose black trousers.

Yes, let’s begin. A new voice tinkles like wind chimes, accompanied by the scent of camellia. The bright ember of my yin soul dances in mid-air, circling the confines of the courtyard. She comes to rest beside the old scholar, a schoolgirl of fifteen with deep brown eyes below wispy bangs, a long pigtail thrown over one shoulder. Her ankle socks and navy uniform blazer match perfectly, her white blouse is spotless.

Leiyin needs to remember, says a third voice. My hun soul flies down from the beams overhead and I feel my hair being pulled, a light, playful tug. Its image joins the other souls. It manifests as a silhouette of light, shaped like a human, as brilliant as the morning sun and as featureless. Before she can ascend to the afterlife, she needs to understand the reason for her detention in this world.

This is punishment? This doesn’t look like hell, I say, feeling a wave of panic. Where is the underground maze? What about the fanged demons, the chambers of torture? What is this twilight existence if not the afterlife?

This isn’t hell, nor is it the true afterlife. My yang soul turns to me, a slight scowl on his seamed face. You could say it’s the afterdeath. And you’re still here because in life you were responsible for a great wrong.

I don’t remember anything about a great wrong. Bewildered as much as indignant, I want to remember my life. Surely I was not, had not been, a criminal.

Soon you’ll remember everything and so will we. My yin soul pulls the ribbon off her pigtail and shakes out her hair. She begins braiding it again. Relive your memories. Only then will you understand what you must do to ascend to the afterlife.

And why do I need to ascend anyway? I know I sound sulky, rebellious.

As soon as I ask this question, an eager swirl of emotions radiates from my souls. In my mind’s eye I see them, three red sparks lifting into the air toward a portal that spills golden light over the horizon. Beyond the portal flicker tantalizing glimpses of grassy landscapes, mountain lakes, and eternally blossoming orchards. This vision makes me yearn to rise up toward that portal and join my souls. Now I understand the restlessness that invades my being, an upward pull I can’t follow so long as the manacles of my sins weigh me down to this world.

We must ascend. Reincarnation awaits us in the afterlife. My yin soul spins so that her pleated skirt twirls up around her, a circle of navy blue. There, we will have a chance for new lives, new hope. But if we stay too long in this existence . . . As her voice trails off, I hear in it a small tremor.

First, she must remember, my hun soul interjects. It reaches out a shining limb and pulls my hair again, this time a firm and peremptory tug. You must understand the damage you did. Then you must make amends to balance the ledger. Only then can we ascend together to the true afterlife.

So we will go together? You won’t go now and leave me here? Relief.

We are your souls, we’re part of you, my yang soul snaps. We can’t leave until you do. He glares at me through moon-shaped lenses.

Don’t mind yang, says my yin soul, who has finished braiding her hair. He’s not happy unless he’s berating someone.

Where should we begin? my hun soul asks. On the day of the party?

Yes, the day of the party, the other souls agree.

The day you first stepped off the path that had been paved for you, my hun soul says.

I have no choice. How else can I reclaim my memories, discover what to do next? At this moment I can’t even remember what Weilan looked like as a baby.

My yin soul sinks to the floor and tucks her knees under her skirt, a child waiting to hear a story. My yang soul settles on a stool near the door and brushes a cobweb from his black trousers. My hun soul drifts to the altar, and with a single bright fingertip gently strokes my name tablet.

Suddenly I’m standing on a street lined with sycamore trees and high, whitewashed walls. I’m watching a schoolgirl climb down from a rickshaw. But in that same moment, I’m also that girl, my foot about to touch the curb.

I know everything about my life before that moment.

I know nothing of what is to come.

Changchow, 1928

For once I had been eager to leave school and get home. I jumped off the rickshaw as soon as it stopped outside the walls of our estate and darted through the wicket gate, dashing past Lao Li, who sat on guard just inside the entrance.

“No need to rush, Third Young Mistress,” the old gatekeeper called after me. “The guests won’t be here for at least two hours!” For the party, he would change into an immaculate house uniform of grey tunic and trousers. He would push open the huge front gates while other servants swarmed to the entrance to guide carriages and sedan chairs into the forecourt and out again, smooth and practised as clockwork.

The party wasn’t my only reason for hurrying. Father had promised to give me his decision today. I sprinted through the courtyard, then past the formal reception halls, and through to the next garden. I had just turned seventeen and was trying to be mindful of my dignity. I hadn’t jumped the boxwood hedge in years, but on this day I hiked up the skirt of my qipao and prepared to take a shortcut.

Hold, I beg my souls. Hold this flow of memories and let me look at my home again.

I want to see the entire property as it was that day. The world of my childhood lies enclosed within its walls: recollections of bare feet on cool moss, a grove of green bamboo, my face pressed against tall windows, watching raindrops gather in pools on a marble terrace.

Obligingly, my hun soul halts the stream of memories and together we rise above the grey roof tiles to view my home as it was. I see myself below, pigtails streaming and skirt yanked up my thighs, about to hurdle a two-foot hedge. I see my family’s estate, its perimeter bounded by whitewashed brick walls, the heavy wooden gates banded with brass studs. I catch glimpses of quiet streets outside, lined with tall, leafy sycamores and other walls, other homes.

The Old Garden is at the centre of our property, a huge private park with a man-made lake at one end large enough to contain an island of reeds and willows, home to families of ducks. Arranged around the Old Garden are a dozen courtyard houses, each nestled beside its own, smaller garden.

In that moment of suspended memory, one of my great-uncles is halted in mid-step on his stroll around the lake, a servant boy behind him toting books and a canteen of water. Two of my aunts rest in the shade of the bamboo grove, admiring a stand of blue irises. On one of the terraces facing the Old Garden, my nieces skip rope, arms raised, motionless.

I turn my gaze across to my own home, built thirty years ago when my father returned from university in Paris, in love with honey-coloured stone and all things French. We lived in a villa surrounded by a green lawn that rolled down to rose gardens bordered by boxwood hedges. It was all straight lines and precise geometry, even to the clipped Italian cypresses lining the walls. The rose garden blooms in masses of colour, extravagant and gaudy compared to the restrained serenity of the Old Garden.

Then my hun soul allows the stream of memories to flow again.

I watch my memory-self leap over the hedge, and at the same time, I feel boxwood leaves brush past my ankles and the giddy, unreserved joy of being seventeen again.

I ran into the villa and nearly crashed into Nanny Qiu.

“Wah, wah, Third Young Mistress! Why are you running inside the house like some mad animal?”

“I need to see Father. Right now. Is he in his study?”

“Yes, but the Master is with your brothers.”

That meant Father was discussing family finances.

“Oh. Has Eldest Sister arrived?”

“She is helping Second Young Mistress get dressed.”

My sister Gaoyin was home from Shanghai for the party. I nearly slipped on the cool marble of the circular staircase as I dashed up to the western wing of the house, where my second sister, Sueyin, sat at her dressing table. Gaoyin stood behind, pinning up her hair. They both turned to me, smiling in welcome.

How could I have forgotten their lovely faces, even for a moment, even in death?

Everyone agreed that my mother had been the most beautiful woman ever to marry into our family. I was four when she died, and retained only the haziest of impressions of her: a pale oval face, the scent of osmanthus blossom. Her exquisite features lived on, celebrated in family legend and preserved in a few sepia-toned photographs.

Before they turned sixteen, my two older sisters, near replicas of our mother, were famous already in Changchow. Their faces were perfect ovals, their eyes long-lidded beneath delicately arched eyebrows. The most nuanced of details differentiated their features and those details bequeathed to Sueyin an unearthly beauty. Her nose was just slightly longer, her mouth a little wider than Gaoyin’s. I’m considered pretty, but beside my sisters, I was quite ordinary: my eyebrows heavy, my forehead a bit too high. But we Chinese like groupings of three, so I was lumped in with them and we were known as the Three Beauties of the Song Clan.

Thus when elderly aunts or servants chastised me, they might say, “Your mother, whose skin put white jade to shame, always stayed out of the sun,” or, “Your mother, whose graceful walk poets compared to the swaying of willows, never would have galloped down the hall like a demented mule.”

Their words never failed to remind me that I could only aspire to such perfection, for in addition to an excess of beauty, my mother had been blessed with a sweet nature and fertile loins, delivering two sons before both she and her third son died during childbirth. That she also bore three daughters was of little consequence.

“Let me look at you,” my eldest sister said.

But I was the one staring in admiration. Gaoyin’s long, glossy hair, once habitually twisted up in a knot, now grazed her jawline in soft waves, a modern and sophisticated hairstyle like those we saw on models in the Shanghai fashion magazines. But she was far more beautiful than any of them.

She hugged me, an embrace of bergamot and jasmine.

“How delicious, Eldest Sister. What’s that new perfume?”

“It’s called Shalimar,” she said, pleased. “Shen brought it back for me from France.”

“What does Father think of your short hair?”

She tossed her curls. “Shen likes it, and my husband’s opinion is what matters now. But tell me, little bookworm, what are you reading these days? Is it something I would enjoy?”

“Probably not. But at least you wouldn’t need to read it in secret, since you’re married. It’s a translation, a Russian novel called Anna Karenina. It’s banned from the school library.”

“But you bought a copy anyway?”

“No, a classmate lent it to me.”

Gaoyin’s laughter sent her curls bouncing against her neck. She turned back to pinning up Sueyin’s hair, which she had arranged into a knot secured by jewelled combs.

Even barefaced and wearing the dowdiest of dresses, Sueyin turned heads. Gaoyin and I shared her pale skin, but our elderly aunts assured us that Sueyin was the only one who had inherited my mother’s lustrous complexion. I never understood the point of envying Sueyin. She was simply unattainably beautiful. Tonight her face glowed radiant as white jade against the high neck of her emerald-green qipao. The dress was a modest ankle length but cut close to show off her slim figure.

“Well, Third Sister,” said Gaoyin, “what will you wear tonight?”

“I’ll just wash my face and go down in this.” My hand swept the front of my dress, a plain qipao of navy blue, its only ornament a row of turquoise cloth-covered buttons fastened across the bodice.

“Third Sister! This is Sueyin’s engagement party, not a family dinner.”

“All right, then. I’ll change into my formal school uniform, you know, the blue blazer and plaid skirt.”

Before Gaoyin could open her mouth to rebuke me again, Sueyin spoke up.

“Please, Little Sister. Wear something special.” Her perfect eyebrows drew closer in the tiniest of frowns. “Or you’ll look like a high school student.”

“I am a student.” But Sueyin, selfless as she was beautiful, hardly ever asked me for favours, and I relented. “For your engagement party, Second Sister, I’ll wear a nice dress.”

When Sueyin turned eighteen, a flood of matchmakers began arriving at our gates from as far away as Hangchow and Shanghai. Father had settled on Liu Tienzhen, the only son of Judge Liu, whose family was even wealthier than ours. The judge was famously traditional and hadn’t wanted the betrothed couple to meet before the wedding. But in deference to Father’s request, Judge Liu had agreed to allow Sueyin and Tienzhen to meet beforehand so they wouldn’t be total strangers on their wedding day. That was the reason for this evening’s party. Gaoyin insisted on calling it the official engagement party.

I hoped Father would put off any engagement or marriage for me until I’d finished my education. I sat up on the bed.

“I need to see Father. Right now.”

They both turned to me, with identical enquiring looks.

“Father said he’d give me his decision today. Whether I can attend teacher’s college. I’ve applied to Hangchow Women’s University.”

“His answer will be no.” Gaoyin’s self-confident tone made me want to stick my tongue out at her.

“Third Sister is always top of her class. There’s a good chance Father will agree.” Sueyin smiled in my direction.

At that moment old Nanny Qiu came puffing to the door. “Wah, wah, Third Young Mistress, what are you doing? The Master wants to see you now. Then you must take a bath, you must be covered in sweat after the way you galloped up here. Your mother—”

“Yes, yes.” I got up hastily. “Nanny, will you come in later to fix my hair?”

But I had a parting shot for Gaoyin.

“Just because you didn’t go to university doesn’t mean Father won’t let me. For one thing, my grades are much better than yours ever were.”

She threw a pillow at me. I ducked and ran out, giggling.

The door to Father’s study was ajar and I could hear my eldest brother’s voice.

“Chiang’s army lost so badly to the Japanese in Jinan earlier this month. I’m sure it’s added to Japan’s certainty that China is theirs for the taking. The Japanese may be trying to downplay the whole thing by calling it the May 3 Incident, but I’m sure it means war with Japan, sooner or later.”

“We need to consider both Hong Kong and Singapore. The Japanese wouldn’t dare invade British territory. Our assets would be safer overseas.”

“I agree, Father, but I still think we should buy property in Hawaii or San Francisco. America is even safer.”

The voices belonged to my father and my eldest brother, Changyin, who were both standing over Father’s big lacquered table, looking down at piles of paper. I knew the civil war was ruining many families, some even wealthier than ours. But with Father and Changyin looking after our investments, surely we would be all right.

Father was plainly clothed, as always. It was hard for me to reconcile this dignified presence, whom I had never seen in anything but a traditional changshan gown, with photographs of Father as a student in Paris, a grinning young man resplendent in striped shirts and embroidered waistcoats. Tonight, because of the party, his gown was silk, dark grey woven with a design of bamboo leaves. He wore shoes with cloth soles, a pair that Stepmother had finished making just the day before. His goatee was newly trimmed.

My eldest brother was the only one of us who took after Father, with his heavy, square face, heavy eyebrows, and square, solid build. Like Father, Changyin wore a changshan. But unlike Father, who wore loose trousers beneath his changshan, Changyin favoured a half-Western look. Tailored gabardine trousers showed below his ankle-length gown, their cuffs neatly settled on polished black wingtip shoes. Changyin was only twenty-seven, but to me he seemed decades older. He shared with Father the work of managing our family’s wealth and I could already see the strain in his ruddy complexion. His carefully trimmed hair showed signs of thinning and would be as grey as Father’s before he turned forty.

My second brother, Tongyin, lounged in an armchair, staring out the French doors and not even trying to conceal his boredom. Tongyin had long since abandoned traditional dress. His summer suit of pale linen was brand new and his yellow paisley tie matched the hatband on his straw panama hat. His hair was shiny, slicked back. He had become even more of a dandy since attending university in Shanghai. Much as I detested him, I had to admit Tongyin was very handsome; he had inherited our mother’s cheekbones and her long, delicate fingers. At the moment, the straw panama twirled on one of those fingers. He exhibited no interest in our family finances beyond what was deposited in his bank account each month, yet Father always included him in their discussions.

“Are you going to the party wearing that?” Tongyin had noticed me at the door. Although he was only two years my senior he always treated me as though I were a child.

“No. Are you going to the party smelling like that?” I couldn’t help it. Tongyin was the vainest person alive. And he tended to dab on too much cologne.

“Eh. That’s enough.” From the other end of the table Changyin shook a finger at us. An order from Eldest Brother was as good as an order from Father and we held our bickering while Changyin and Father finished talking.

Dismissed by a casual wave of Father’s hand, my brothers left the room. I stuck my tongue out at Tongyin, and then quickly composed myself.

“Father, how are you feeling today?”

He smiled, an indulgent and affectionate smile. Surely he had decided in my favour.

“Third Daughter. Sometimes I forget you are already a young woman. Where have all my little children gone?”

“There’s still Fei-Fei, Father.” He nodded, but I knew that Fei- Fei, who was the daughter of his concubine, my stepmother, held a smaller place in his heart.

“The house feels empty already when I think of Sueyin getting married. It would be even emptier if you went away to school.” My mouth opened, but I bit my tongue.

“Third Daughter, you do not need a career. So there is no point in spending tuition fees and boarding-school fees on more education.”

I looked down at my lap, struggling to hide my disappointment. Hadn’t I made it clear to Father how much I wanted to attend university? I had plans already to share a room with my best friend, Nanmei. What would I tell her now?

He lifted my chin with a forefinger and tapped me playfully on the nose. “No sulking, little bookworm. You’re a clever young woman with many interests. Tomorrow or next week you will find another pastime worthy of your intelligence.”

“Father, I don’t consider teaching a pastime.”

“Leiyin, you will be a wife and mother. You won’t need to earn a living.”

His tone was mild, but he had used my name. There would be no further discussion.

I just had to convince Father that university wasn’t a frivolous whim. Then I looked at the table, the stacks of paper, and the old abacus with ivory beads that had once belonged to my grandfather. I looked at Father. He had so much on his mind. But there had to be a way.

“Now go see your stepmother,” he said. “She wants a word before the party.”

I was dismissed.

Stepmother sat at one of the three round tables in the small dining room. Lu, the head house servant, stood beside her, as upright as a general on horseback, the pleats of his trousers as sharp as bayonet blades. He gave me the slightest of bows and continued addressing the house servants lined up along the wall. They stood at attention, shoulders stiff and straight, hands crossed behind their backs.

“Finally, if a guest asks for something and you don’t know where it is or what it is, just bow and say ‘Right away.’ Then come and get me immediately. I’ll be at the side entrance of the dining hall. Now go wash up and put on your best uniforms. Girls, remember to pin up your pigtails.”

They filed out under Head Servant Lu’s critical gaze. I counted sixteen. Stepmother had borrowed staff from other houses for the party. Lu made his bow to Stepmother and another, deeper one to me and then joined the end of the departing troop.

Stepmother was thirty-three, only six years older than Changyin. From a distance, however, her old-fashioned gowns and matronly hairstyle gave the impression that she was a generation older. Her looks were comfortably plain, her smooth flat features serene as a Buddha’s and just as impenetrable. Her eyes were remarkable, large and deep-set. Hers was a demeanour that soothed tempers and quieted arguments.

If we hadn’t been so fond of Stepmother, we would have called her by the lesser family title of Yi Niang, for she was only Father’s concubine and not eligible to be addressed as Stepmother. If she had given birth to a boy instead of little Fei-Fei, Father might have married her and she would be his first wife now. I knew that Stepmother, who was from a family of cloth merchants, had never expected to be made a wife, even after our mother died. If Father married again, it would be to a woman of our own class, but I hoped he wouldn’t. I’d hate it if a new wife proved unkind to Stepmother and little Fei-Fei.

“You wished to see me, Stepmother?”

“Yes, Third Stepdaughter. Once your second sister is married, you’ll be the only daughter of the house. You’ll have to take on hostess duties, so you could begin tonight if you’re willing.”

“Of course, Stepmother. Tell me what I have to do.” I sighed. I’d have to stay for the entire party. When would I find time to finish Anna Karenina?

“Leiyin. Your father expects it of you.” Her amused smile said she knew I wasn’t enthusiastic. “Just take this list and study it before you come downstairs to the party.”

I glanced at the list, then over at the door. The scent of Shalimar announced Gaoyin’s entrance.

“Stepmother? Ah, Third Sister, you’re here too.” For a moment, Gaoyin looked strangely shy. “It’s not important. I just wanted a few minutes with Stepmother.”

I stayed in my chair. Gaoyin indicated the door with the slightest tilt of her head.

I rose reluctantly. “Well, I’d better go upstairs and bathe before Nanny gets upset with me again.”

The party didn’t need my attention. I doubted the servants needed any supervision, given how thoroughly they had been drilled by Stepmother and Head Servant Lu. I scanned the drawing room anyway, just to be sure.

Three crystal chandeliers, their prisms and beads polished to dazzling clarity, formed the centrepiece of the drawing room. Porcelain vases filled with flowers from the garden decorated every alcove. Framed by potted palms, a string quartet churned out popular tunes. They sounded rather dispirited, so I smiled to show I was paying attention, and the tempo picked up.

A maid moved through the crowd, emptying ashtrays almost as soon as they were dirtied. So silent and unobtrusive that they were nearly invisible, servants in cloth-soled shoes padded over the shining parquet floors carrying trays of shrimp toasts, tiny blintzes topped with caviar, and devilled quail eggs. The dinner itself would be Chinese, of course. It was fashionable to serve Western-style appetizers, but we couldn’t inflict an entire meal of foreign food on our guests.

Gaoyin wore a cocktail dress of dark grey silk that would have looked matronly on anyone else. I knew she wanted to be sure Sueyin wouldn’t be upstaged, but really, there was no need to worry. Sueyin looked like a heavenly handmaiden from the court of the Jade Emperor. Her fiancé hardly took his eyes away from her. Liu Tienzhen wasn’t as tall as my brothers, but he was very handsome. He had smooth skin and the sleek features of a matinee idol. He inclined his head toward her with a gentle but slightly possessive air. The soft, dreamy look in his eyes when he gazed at her pleased me. Of course he adored her already, how could anyone not? They made an impossibly beautiful couple.

Tienzhen didn’t quite take her hand, but he did touch her elbow as Sueyin led him outside to walk in the garden. The sky had turned cobalt blue, now dark enough for the moon to be seen, a shy crescent of silver. The evening air was heavy, it would rain before morning; but the peonies and early summer roses were in bloom, and the garden would be steeped in fragrance.

If the loud drone of conversation indoors was any indication, the guests were mingling very well. Father and Changyin had included several poets and writers on the guest list, regular attendees of Father’s renowned weekly salons. Father always said one could rely on passionate literary types to liven up conversation. The party was going so well I wondered if I could slip away to finish Anna Karenina. I had to return it soon to Nanmei, for there was a long queue of girls waiting their turn to read this scandalous book.

Circling the room, I caught fragments of conversation. On the banquette, my father and Judge Liu were deep in a discussion about the legal system of the Song Dynasty.

“I put it to you, honoured Judge, that despite the turbulence of the era, the Song legal code was essentially the same as the legal code of the Tang Dynasty.”

“Both were based on the Northern Zhou codes, I agree, but you must admit the Tang adhered more strictly to the Confucian rules of social order.”

Next I passed by Changyin and Gaoyin’s husband, Zhao Shen, who were with a group of men engrossed in a loud debate about the conflict between the Communists and the Nationalist government.

“The Communists are recruiting college students as activists. Pay their tuition, let them finish school, then send them out to the countryside as teachers to spread Marxism.”

“After the Nationalists carried out that purge last April, rounding up members of the Communist party and executing them like that, you can bet the Communists will never trust them again.”

“The Reds are calling it the Shanghai Massacre, you know. I’d be nervous if I was a member of the left-wing faction of the Nationalist party. They’re next in Chiang’s line of fire, for sure.”

“That coalition of three factions was never going to hold together. Now they’re each claiming a different capital city. Peking, Nanking, Wuhan—how do you think that makes us look to the rest of the world?”

It made my head hurt keeping track of our politics, but I did try. After all, I was born the year the Nationalists overthrew the Qing Dynasty and we became a republic. For a decade, Nationalists and Communists had been united, and some of the Communists had even joined the Nationalist party to form a left-wing faction. Then Sun Yat-sen died, the alliance fell apart, and I still wasn’t sure why each side accused the other of betraying Sun’s Three Principles of the People.

The one thing I did understand was that I had to do my part to bring our young nation into the twentieth century. Our class had studied an essay written by Madame Sun Yat-sen about women taking an equal role in building China. Ever since then, Nanmei and I had been determined to become teachers. I just had to make Father understand.

If I had a hard time keeping up with politics, Tongyin didn’t even try. Outside, a handful of young men lounged on the terrace, slouched in the wicker chairs, their fashionable shoes propped up on the coffee table. One of them flicked a cigarette butt into the peony shrubs. Half-finished drinks cluttered the marble paving. In the mild evening air their laughter rang noisy and raucous. Tongyin was the loudest of the lot, and even though his back was to me and I couldn’t hear his words, I knew he was telling a smutty story.

The scent of Shalimar told me that Gaoyin had come to my side. She swept her gaze across the terrace. The young men facing us noticed her scrutiny, and there were a few wolf whistles, quickly hushed. One of them bowed in exaggerated courtesy.

“Let’s go inside.” She pulled me around. “Come meet my friends.”

It was evident from the bursts of laughter and shocked gasps we heard as we approached that the women gathered in the corner were catching up on gossip.

“My goodness, is that Yen Hanchin?” A woman I knew only slightly, dressed head to toe in pink, asked the question, avid interest evident in both her tone and the gleam of her eyes as she gazed across the room. “That is him, isn’t it, Gaoyin? Over there, beside your brother? I’d heard he was back from Russia.”

Yen Hanchin. His name was on my copy of Anna Karenina, he was the translator. I stared in the same direction. Across the room a stout, slightly balding man leaned in confidingly toward my brother, cigarette ash dropping on the Persian carpet as he spoke. So that was the translator of the forbidden novel. How disappointing. I had imagined someone more haggard, a starving writer and political activist. The Chinese version of Levin’s brother Nikolai. I’d heard Yen Hanchin harboured leftist sympathies, another reason why his book was banned from our library.

“Yes, Changyin knows Yen Hanchin slightly,” Gaoyin said. “They met at a poetry reading. Yen’s a very fine poet, apparently. But he’s only become famous since he translated Anna Karenina.”

“I suppose that’s better than being infamous for other things,” said the woman in pink.

It had been a mistake to stare for so long. Gaoyin noticed my curiosity. “Would you like to discuss Anna Karenina with Yen Hanchin, Third Sister?”

“No, Eldest Sister. Anyway I haven’t finished reading the book.” I didn’t want to get trapped talking to some middle-aged scholar, infamous or not. He might drone on about pre-revolutionary Russia and its depiction in the modern novel. Our headmistress had tortured us once with a lecture by just such an academic and Nanmei had had to pinch me every five minutes to keep my head from nodding onto my chest.

“Come.” Gaoyin took my arm. Her eyes glittered and her cheeks were flushed. When she drank wine, no amount of face powder could hide the effects.

“Oh, Eldest Sister, I’m supposed to be supervising the servants.” But she pulled me across the room, her high heels giving her more purchase on the Persian carpet than I had with my slippery flat soles.

“Yen Hanchin, here is someone you should meet.” One of the men turned around at her greeting. It was all I could do not to gasp.

Not the stout balding man. Not a Nikolai.

A Vronsky.

Tall, with hair just a bit too long. He was in his late twenties, perhaps as old as thirty. His shabby linen jacket made all the other men, in their tailored suits and silk ties, look merely ornamental. He was lean and lightly tanned. Beneath intense brown eyes his cheekbones were sharp, angled escarpments. He was both beautiful and intoxicatingly masculine. He was a poet. For several moments I couldn’t take my eyes away from him. Was this the feeling that swept over Anna each time she beheld Vronsky?

He smiled down at me, the smile of a man accustomed to the admiration of women